“A Safety Net for Travelling Idiots” - Prof Meic Pearse

The tale I have to tell is one which my Balkan friends will find so utterly unremarkable that they will wonder why I bother to relate it at all — but which will cause the eyebrows of my American, British, German etc. friends to lurch heavenwards at several points.

And really, that discrepancy in the barometers of astonishment is more worth the pondering than the story itself.

A couple of years ago, I was one of the speakers at a conference in Ohrid, that beautiful city in North Macedonia that overlooks the lake and the Albanian mountains on the far side. At the end of the four days, I had made some rather tight travel arrangements. The plan was to leave the large hotel where we had all been staying — and where the conference had taken place — to get an early morning bus from Ohrid to the capital, Skopje. There I planned to take a group of friends to lunch — following which, one of them would whisk me to the airport for my flight.

My friend Kosta (yes, yes: that's Gabi's Dad) drove me into town from the lakeside hotel, and shepherded me onto the bus. And as the vehicle pulled away I realised, not for the first time in my life, that I am a complete idiot.

My passport was not in its accustomed hiding slot in my bag. For I had neglected to retrieve it from the hotel reception as we left. Without it, boarding my flight — not to mention the other borders I would need to cross shortly after that — was out of the question. For maybe five or ten minutes, as the bus chuntered out of Ohrid, I succumbed to blind panic. And then, I hit upon exactly what I had to do.

I sent a text message to Kosta, confessing all. Could he, perhaps, send the passport after me, on the next bus to Skopje? He could, and he did.

My friends met me in the capital and, as they took me to the restaurant where several branches of an illustrious family were gathering to eat at my (not very considerable) expense, I explained the delicacy of my situation.

"No problem." It is the mantra of the Balkans. Here, we can manage everything. Mostly because we have to.

Half-way through lunch, phone calls were made; watches were checked. The next bus would by now be about to arrive from Ohrid. One of the party departed to the bus station, mid-meal, to meet it. Half an hour later, he was back, with my passport in hand. I would now be able to catch my flight — and thus fulfil my intricate pattern of post-flight appointments — after all. My self-created crisis was over.

And yet almost every stage of that adventure would have been unthinkable in Berlin, or Birmingham, or ... ummm, Birmingham. In the first place, how dare a hotel hang on to a guest's passport beyond the absolute minimum necessary for registration? Is this a hangover from Communism? Or does it have so little in trust its guests that it holds their vital documents hostage against a moonlight departure?

In the second place, no western establishment would have handed over such an important document to anyone but its owner. Even presupposing the propriety of the hotel hanging on to passports for so long, if a person had failed to collect it upon departure — well, he or she would just have to come back for it. (And, in my case, that would have meant missing, not just my lunch with friends, but my flight.) In the Balkans, however, such things are possible. If Kosta says "My British friend has forgotten to collect his passport and would you mind giving it to me?" — well, here you are, Sir.

In fairness, not just anyone could do this — even in the Balkans. If the person requesting my passport from the front desk staff of a prestigious hotel had been, say, one of Mančevski's peasants (If you don't 'get' that little joke, you have some excellent Macedonian movies waiting for you to catch up on), he would likely have been given short shrift. The same might have been true, I fear, if the person had been (let us say) of the 'wrong' ethnicity. But my friend Kosta is visibly a Man of Authority. Gentle as a lamb, he never raises his voice. Nor ever needs to. People of all ages and both sexes are simply inclined to defer to whatever he asks. (Except Gabi. Obviously.)

In the third place, giving an envelope containing who-knows-what to a bus driver and telling him that he will be paid when it is collected at the end of the journey sounds to western ears simultaneously corrupt and far too trusting — on both sides of the bargain. How is the bus driver to know if he is being gulled into moving drugs around the country, or some explosive substance? How is the sender to know that the driver will not simply make off with the goods, or pretend that he never received them in the first place? But in the Balkans, the practice of sending goods by this method — which is, when one thinks about it, both quicker and cheaper than the postal service — is standard (if informal) procedure. It is also a handy supplemental income for bus drivers. And if it is corrupt, then it certainly depends on absolute honesty by all parties.

Fourthly, when the bus driver arrived in Skopje, he meekly handed over the package to someone who was not its owner and might have been anybody. But again....

Reflecting on it afterwards, I was torn between feeling an utter fool for my initial moment of madness, and congratulating myself for knowing what to do, and being possessed of the social capital — a network of friends — to do it. For, make no mistake, a mere tourist would have been unable to draw upon a cast of reliables to retrieve the blunder.

One way and another, we need to cope with a lot in the Balkans. But at least it comes with safety nets.

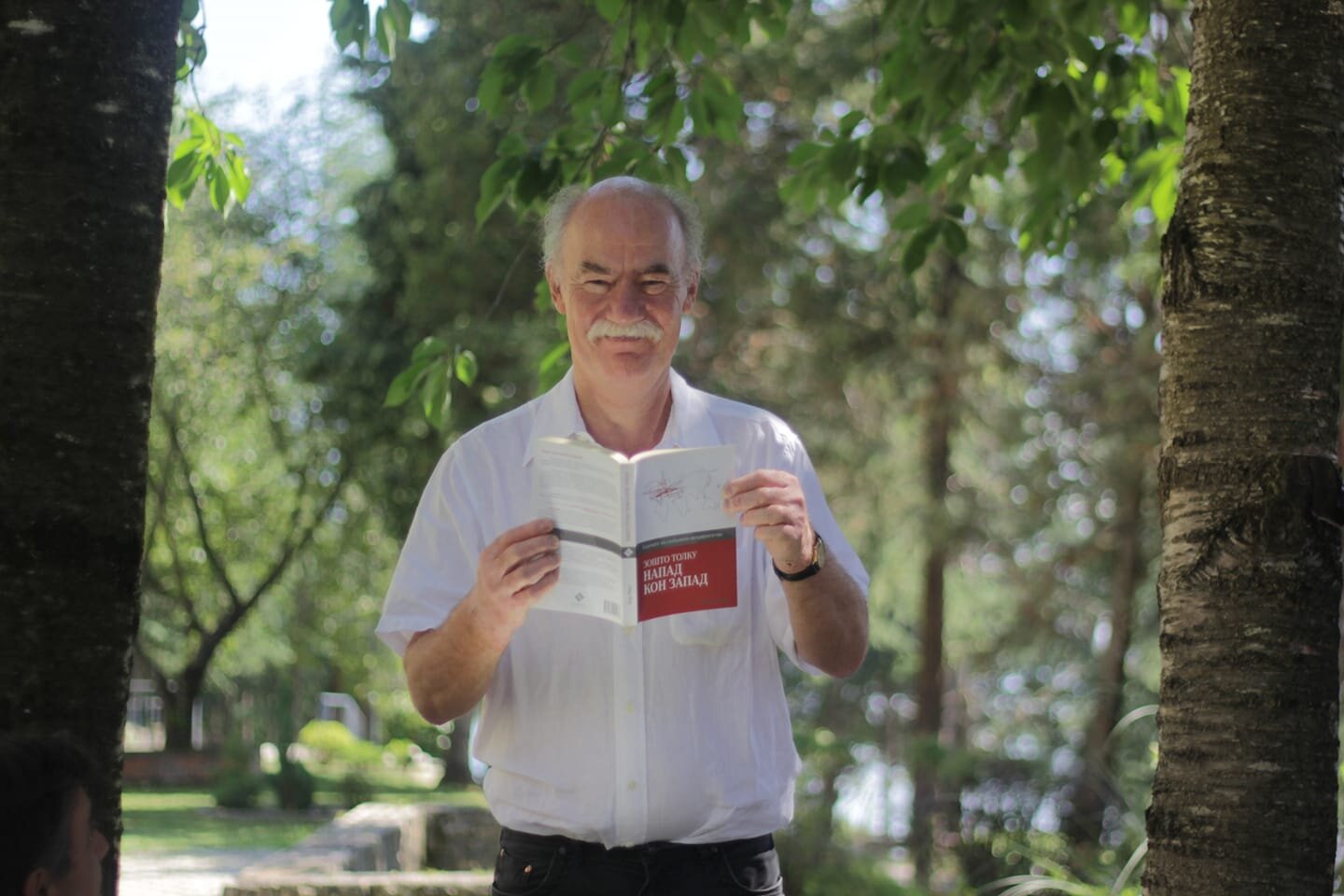

Meic Pearse (M.Phil., D.Phil., Oxon.) was recently Professor of History at Houghton College NY, until he was retired early in 2019, on health grounds: they were sick of him

The author of seven books, most notably Why the Rest Hates the West (InterVarsity, 2004), he speaks German, some Serbian/Croatian/Bosnian, some Welsh, and has been known to embarrass himself in Italian and French. In his spare time, he enjoys not watching television.

He truly is as unjustly horrible to everyone as this article makes him sound. Except to Gabi, who deserves it.